Remembering a Christian: The Story of Yu Kuliang

“The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (John 3:8).

Silently and at first imperceptibly, the wind of the Spirit blew into the isolated cell of a self-tortured idol worshipper in China.

Yu Kuliang lived with her mother in Purity Hall, a retreat built for them by her father’s aristocratic family. He died when Kuliang was just an infant. Her grief-stricken mother chose to live in seclusion, devoting herself to the search for truth as a Taoist nun and raising her little daughter to do the same.

Kuliang learned to read at an early age and spent her days alternately pouring over religious texts and kneeling before the household idols. As she grew up, her zeal surpassed even her mother’s. She always kept three sticks of incense burning—one for Taoism, one for Buddhism and one for Confucianism—the three religions of China.

As a young woman, Kuliang retreated into a small room in the house with nothing but her sacred texts and idols. For three years she had no contact with anyone, even her mother, and did not leave her tiny cell. After completing her three-year isolation she came out into the house for one year, and then went back into this self-imposed confinement for another three years. She repeated this four times, spending a total of twelve years without human contact. Her desire to find truth was so desperate that she even offered up bits of her own skin as a sacrifice to the gods. Her face and body were covered with scars.

When Kuliang was 32 years old, she discovered that she had an aunt and cousin living in Kiukaing. The only family she had ever known was her mother. Actually, because of her extreme isolation, her mother was the only person she had ever known, with the exception of her childhood tutors. Astonishingly, Kuliang decided to leave Purity Hall and pay a visit to Shi Meiyu and her mother.

Though they were cousins and born the same year (1873) in the same town, Meiyu’s life could not have been more different from Kuliang’s. Both her parents were Christians, and made sure their daughter was fitted for service to the Savior. Meiyu had been educated by missionaries and traveled to America to attend medical school. Now she was running a mission medical clinic. Her mother was a Bible-woman, a sort of hospital chaplain who tended to the souls of sick women while Meiyu tended their bodies. Meiyu and her mother invited Kuliang into their lives and gradually coaxed her out of isolation.

Kuliang began to attend church and spent time shadowing Meiyu at the clinic. Meiyu invited Kuliang to spend a week in her home, and to her utter amazement, Kuliang agreed. She had never spent a single night away from Purity Hall, but her eagerness to learn more about the living God outweighed her apprehension. They had long talks about what Kuliang had been reading in her new Bible. All the energy she had once poured into studying the three religions of China was now diverted into study of the living Word of God.

When Kuliang returned to Purity Hall, she was a different woman. She quit wearing the robes of a Taoist nun and dressed in traditional Chinese clothing. She no longer worshiped or cared for the household idols. She gladly allowed Meiyu and her mother to destroy them and dispose of the temple bell she had used to call her gods from their sleep. The living God never slumbers—she needed no bell to get His attention! For twelve years these idols had been her only companions. Now she looked on in approval as Meiyu and her mother chopped up her wooden Buddha and threw the remains in a ditch.

Kuliang’s mother was furious with Meiyu. “If your God is such a mighty one,” she reasoned, “Why should He be jealous of our poor little idols?” As she continued to talk, Meiyu picked up a stone and a bit of wood from the floor. She spoke quietly to them as the mother continued her speech. Finally, exasperated, the mother said, “What nonsense is this?”

Gently, Meiyu explained. “If you think it nonsense for me to talk to the stone and wood in your house instead of giving you attention, how do you think the heavenly Father feels when you satisfy yourself with images of wood and stone instead of giving that love and devotion to Him?”

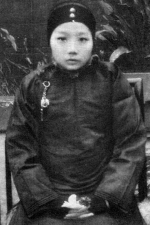

Soon after her conversion, Kuliang contracted tuberculosis. It progressed quickly, but Kuliang assured her mother and Meiyu that she was content in Christ. Just a few days before she died, she insisted on sitting up to have a picture taken in Chinese clothing, since all the previous ones were in the gray robe of a Taoist nun. Kuliang wanted to be remembered as a Christian.

___________________

Information and art for this article came from the book Notable Women of Modern China by Margaret Burton, Fleming H. Revell, 1912